This word doesn’t really exist or have a true definition,

but it seems to encompass all qualities that are related to cancer.

The inherent cancer parts of cancer.

There are so many facets to cancer in general. Each kind of cancer has its own persnickety

descriptions and terminologies.

For example, I can tell someone I had cancer.

If that person asks what kind, sometimes I will respond: blood cancer.

If that someone wants to know the specific blood cancer, I

respond: Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma.

If someone wants to know the staging, I can add that it was Stage 1/e Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma.

If I really want to get detailed, I’ll throw in extra

descriptors: Stage 1/e Mediastinal

(Diffuse) Large B-Cell Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma

See? So many fancy

names and descriptions.

My oncologist did not specifically tell me the fancy

terminology outside of Stage 1/e Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma. It’s possible that he didn’t feel the need to

be that specific. I found out the information

in pieces by gazing at my medical records, conversations with doctors at my

oncology office and those at MD Anderson, and of course research.

As a future librarian, I’m part of a group of people that

will venture forth with the following philosophy: knowledge is power. It’s pretty much ingrained in the ideology of

librarianship, but even outside of librarianship, it’s a giant dose of truth.

However, I have one piece of advice about personal research

regarding medicine: take it with a grain of salt.

It’s incredibly easy to be caught up with WebMD, anything

produced by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the millions of forums

and blogs out in cyberspace.

All of it will scare the crap out of you.

I mean this with no sense of irony as I write a

cancer-related blog. I mean this in

complete sincerity.

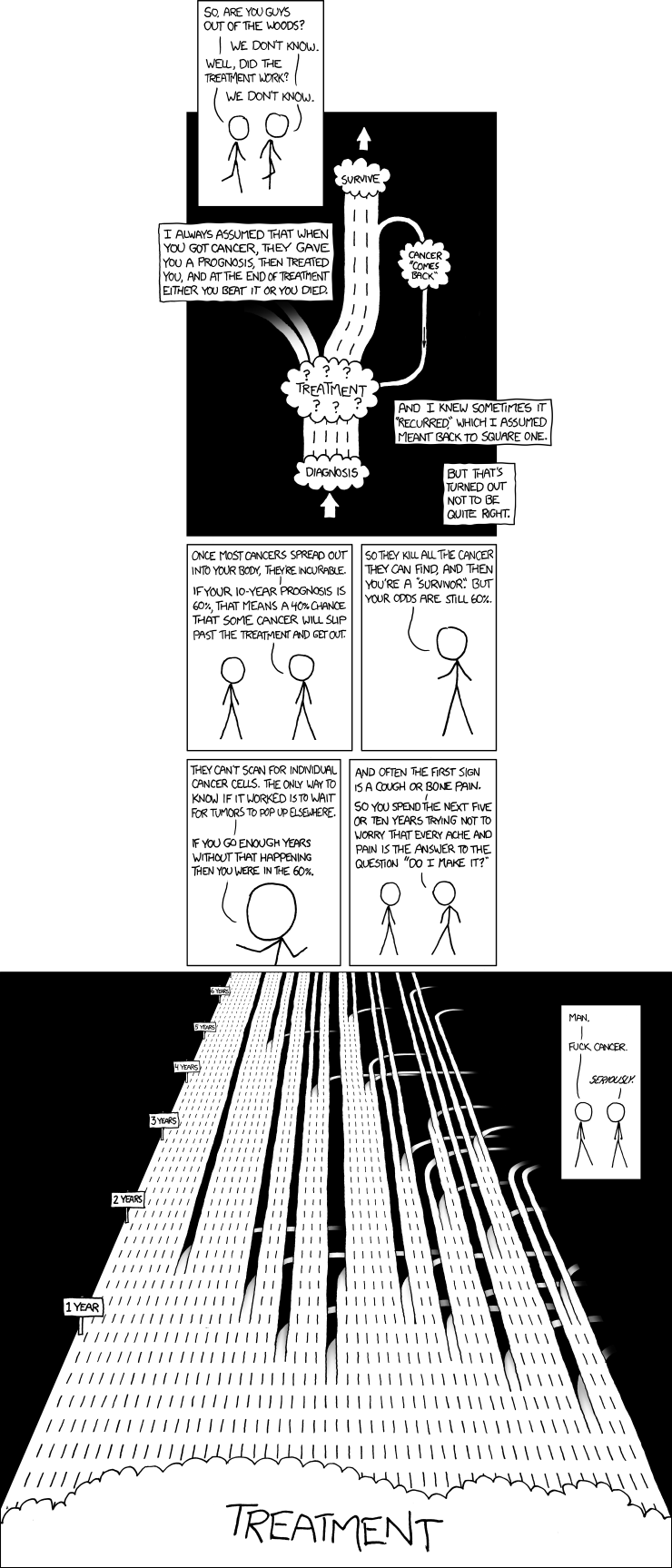

When I was first diagnosed, I gleaned as many information

sources I could find concerning cancer statistics, especially ones concerning

survival rates.

What a mind fuck.

The precious lucid moments I had between treatments

shouldn’t have been concentrating on using my graduate student access to research

academic versions of Medline databases at my university’s library in order to find

prognosis statistics.

I do believe it is empowering to use information sources to

understand cancer causes, symptoms, and treatments.

This might be a philosophy encouraged for doctors as well

since my doctor even gave me a printout from PubMed Health about Non-Hodgkins

Lymphoma during my diagnosis*.

However, to understand medical research is like opening the

server room at any IT department: a lot of friggin’ wires.

I understand this even more since I have been undertaking an

Evaluating Information Services course

this past semester.

For example, I found out there is a whole code of ethics for

research. I think on some shallow level,

I understood this, but one look at this report will tell you that there is no

fooling around:

Aside from approaching a project ethically, one has to take

into consideration the following: previous research (i.e. undertaking enough

reading to make your eyeballs bleed), various research models (i.e. make it so

complicated that no one understands what the hell you are studying), and

statistical analysis.

Statistical

analysis.

It sounds like a root canal would be more fun, right?

The permutations that can result from various data collected

seem innumerable. If you truly look at

data and apply statistical methods to analyze it, there is the possibility that

there are no correlations or too many correlations between data sets.

Considering these concepts in retrospect is illuminating

when it comes to understanding cancer research and statistics. Discovering correlations takes time and

skill. Then to disseminate all the

information to a hungry public eager to learn about their potential longevity

in the face of treatment is an equally difficult task.

It is humbling how carefully these types of research take

place. It is overwhelming to think that

there are so many pieces to take into consideration.

Enough to make me want to shut the hell up about the negative

issues with cancer research.

So, one big thought that I’ve been working through these

past few years post-treatment:

Take it one day at a time, or better yet, one minute at a

time.

Suffering over what could be or what will come next is not a

good solution. I have experience with

this. Before going through biopsy

surgery in August 2011, I tired out my chemo-ridden self with worry:

What if it is still

malignant? I will have to go UT

Southwestern and do a stem cell transplant.

What the hell is a stem cell anyways?

I will live in a bubble and no one will be allowed to visit me. My cats will steer clear of me because I will

have done the human equivalent of “control-alt-delete” and smell weird.

And so forth.

Death was also a consideration. Death tends to swagger around everything we

do as people. The finality of it is

heartbreaking (which is an understatement in itself).

In reviewing survival rates for Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma, the

statistics were, I’ll be honest, a bit grim in some areas, but most positive in

others.

I recently completed a Light the Night walk for the Leukemia

& Lymphoma Society (LLS) in October.

There were different balloons that the walkers could carry depending on

their level of support. Red balloons

went to people who were just plain supporting.

White balloons went to current patients and survivors. Gold balloons went to people who were walking

in memory of someone.

There were a lot of gold balloons during that walk.

The image began to alter as the walk ran out of red balloons

and began handing out white and gold balloons instead, but the initial image of

arriving to the walk comprehending this meaning was tear inducing.

It made me more appreciative of how well I was doing,

despite the annoying little post-treatment symptoms.

Coming back to the biopsy surgery, I recall having to start

the process of training myself not to get too far ahead mentally.

My mind would wander: tomorrow

is my surgery…wait, what am I doing

now? I am cooking. I will concentrate on the boiling water and

pull out the necessary utensils to finish cooking. Hmm, those knives sure are sharp. I wonder if there will be sharp knives used

for tomorrow’s…ok, shut up. You are

boiling water.

I’m learning that this takes practice and cancerness is a

lesson in patience.

Moments are singular pieces of time and moments stacked up are life.

I urge you to look at the moments.

*Note: I just noticed

recently from the URL at the bottom of the printout that was given to me that

the page was last updated in February 2013.

It’s interesting to see the evolution**.

**Additional note:

from a research perspective, it’s beneficial to refer to sources that update

regularly. Otherwise, you might not be

getting factual or up-to-date information.

Just some friendly librarian advice.